1962 War: Why keep Herderson Brooks report secret?

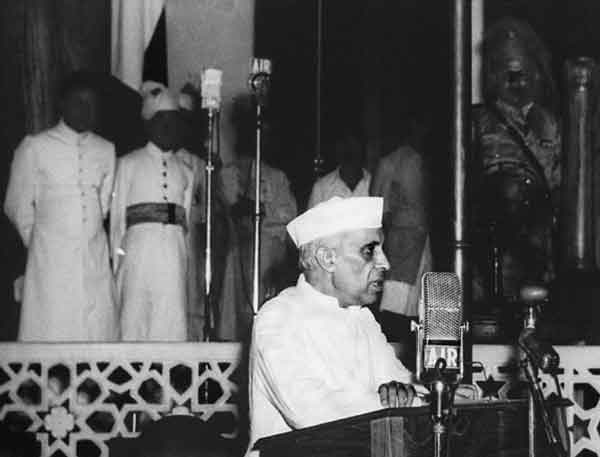

“Even if the founder of the post-independence dynasty, Jawaharlal Nehru may have emerged in bad light in the Henderson Brooks Report, why put a blanket on the entire archives? Are we living in a modern democracy?

…if one day a stable, confident and relaxed government in New Delhi should, miraculously appear and decide to clear out the cupboard and publish it, the text would be largely incomprehensible…” Neville Maxwell

Neville Maxwell: the Authority on the 1962 Conflict

On February 23, 1972 in Beijing, an interesting discussion took place between Richard Nixon, the US President; Dr. Henry Kissinger1, John Holdridge2, Winston Lord3 and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai.

The Premier opened discussion about the Panchsheel Agreement4: “Actually the five principles were put forward by us, and Nehru agreed5. But later on he didn’t implement them. In my previous discussions with Dr. Kissinger, I mentioned a book6 by Neville Maxwell about the Indian war against us, which proves this.”

The US President immediately retorted: “I read the book”.

Mr Antony claimed that the report could not be made public because an internal study by the Indian Army had established that its contents “are not only extremely sensitive but are of current operational value.”

After Kissinger said it was he who gave it to the President, Nixon explained: “I committed a faux pas — Dr Kissinger said it was — but I knew what I was doing. When Mrs Gandhi was in my office before going back, just before the outbreak of the war [1971 Bangladesh Liberation War], I referred to that book and said it was a very interesting account of the beginning of the war between India and China. She didn’t react very favorably when I said that.” Zhou burst into laughter: “Yes, but you spoke the truth. It wasn’t a faux pas. Actually that event was instigated by Khrushchev.7”

“…President Nixon then asked Zhou what Khrushchev had told him. The Premier answered to the Soviet leader’s argument was: “The casualties on the Indian side were greater than yours, so that’s why I believe they were victims of aggression.”

Zhou remarked: “If the side with the most casualties is to be considered the victim of aggression, what logic would that be? For example, at the end of the Second World War, Hitler’s troops were all casualties or taken prisoner, and that means that Hitler was the victim of aggression. They just don’t listen to reason.”

He was so discourteous; he wouldn’t even do us the courtesy of replying, so we had no choice but to drive him out.

Then he quoted again Neville Maxwell who “mentioned in the book that in 1962 the Indian Government believed what the Russians told them that we, China, would not retaliate against them. Of course we won’t send our troops outside our borders to fight against other people. We didn’t even try to expel Indian troops from the area south of the McMahon line, which China doesn’t recognize, by force. But if your (e.g. Indian) troops come up north of the McMahon line, and come even further into Chinese territory, how is it possible for us to refrain from retaliating? We sent three open telegrams to Nehru asking him to make a public reply, but he refused.

He was so discourteous; he wouldn’t even do us the courtesy of replying, so we had no choice but to drive him out. You know all the other events in the book, so I won’t describe them, but India was encouraged by the Soviet Union to attack.”

Thus spoke Zhou Enlai in 1972, giving the Chinese version of the 1962 War, based on the writings of Neville Maxwell.

The Most Well-kept Secret Since Independence

While the information contained in Maxwell’s book originates from the Herderson Brooks Report of the 1962 debacle, this document is today the most well-kept secret of the Indian government.

Does it make sense that an episode commented on by Heads of State of the United States and China in the 1970’s, is still hidden from the Indian public in 2010?

It seems that the official answer is ‘yes’.

In 2008, the Defense Minister, Mr AK Antony told the Indian Parliament that the Herderson Brooks could not be declassified. Mr Antony claimed that the report could not be made public because an internal study by the Indian Army had established that its contents “are not only extremely sensitive but are of current operational value.”

At first sight it seems strange that this 47 year-old report is still of ‘operational value’. The officials who drafted the minister’s reply may not be aware that another report, the Official History of the Conflict with China (1962)8 prepared by the same Defense Ministry, details the famous ‘operations’ in 474 foolscap pages.

“No major security threat other than from Pakistan was perceived. And the armed forces were regarded adequate to meet Pakistan’s threat. Hence very little effort and resources were put in for immediate strengthening of the security of the borders.”

Amongst other things, the ‘official’ Report pointed to the real issue: “No major security threat other than from Pakistan was perceived. And the armed forces were regarded adequate to meet Pakistan’s threat. Hence very little effort and resources were put in for immediate strengthening of the security of the borders.”

Nobody had even thought of China!

The man quoted by Zhou Enlai, Neville Maxwell was the South Asia correspondent for The Times in 1962. He is one of the very few persons to have had (unauthorized) access to the report.

Maxwell commented on Antony’s statement: “Those reasons are completely untrue and quite nonsensical …there is nothing in it concerning tactics or strategy or military action that has any relevance to today’s strategic situation.”

It is worth going deeper into the issue.

What is the Henderson Brooks Report?

A book can help us to understand the background of the Herderson Brooks Report. Between 1962 and 1965, RD Pradhan was the Private Secretary of YB Chavan9 who took over as Defence Minister from the disgraced Krishna Menon after the debacle of October 1962.

Pradhan’s memoirs10, give great insights on the reasoning of the then Defence Minister who ordered the report: “For Chavan the main challenge in the first years was to establish relationship of trust between himself and the Prime Minister. He succeeded in doing so by his deft-handling of the Henderson Brooks’ Report of Inquiry into the NEFA11 reverses.”

Pradhan continues:

[Chavan] learnt some ‘lessons’ that helped him in the conduct of the 1965 Indo-Pak War. In this context, it would be relevant to refer to the Herderson Brooks Report which remains an extremely closely guarded secret till this date12.

Contrary to general expectations the report did not directly indict any political leaders. It was done obliquely.

During one of the debates [in Parliament], the Prime Minister has assured the Parliament that an inquiry will be held into the debacle. After much deliberation, Chavan proposed an inquiry by a committee of two serving army officers rather than a judicial probe or a public enquiry as expected by the Parliament. Further instead of the Defense Minister appointing a committee, he asked the Chief of the Army Staff13 to set-up the same. Accordingly, a two-man committee with Lieutenant General Henderson Brooks and Brigadier PS Bhagat was formed. Both officers had impeccable record of service. Henderson Brooks, an Australian national, had opted to serve the Indian Army after partition and Prem Bhagat was the first Indian officer to be conferred the Victoria Cross during World War II for bravery on the battle field. Their report was presented by the COAS to Chavan in July 2, 1963. The report contained a great deal of information of an operational nature, formations and deployment of the Indian Army.”

As mentioned earlier, the operations are described in greater detail in the Official History of the Conflict with China (1962).14

But Pradhan explains further: “In 1965, it was considered too sensitive to be made public and although outdated today, the report unfortunately remains secret. Pradhan says that he is the only person alive15 who had examined the report16.

The Private Secretary elaborated on the Defence Minister’s sentiments during the following months: “During the conduct of the enquiry Chavan was apprehensive that the committee may cast aspersions on the role of the Prime Minister or the Defense Minister.”

The art of war teach us not to rely on the likelihood of the enemy not coming, but on our own readiness to receive him”¦

“His main worry was to find ways to defend the government and at the same time to ensure that the morale of the armed forces was not further adversely affected. For that he repeatedly emphasized in the Parliament that that the enquiry was a fact-finding one and to ‘learn lessons’ for the future and it was not a ‘witch-hunt’ to identify and to punish the officers responsible for the debacle.

It was a tribute to his sagacity and political maturity that he performed his role to the full satisfaction of the Parliament and also earned the gratitude of the Prime Minister. Some lessons that he learnt are be found in the statement he presented to the Parliament. But it is also a fact that while doing so, he also suppressed certain critical observations. A few words about those might throw light on Chavan’s conduct at political level in the 1965 war.

Contrary to general expectations the report did not directly indict any political leaders. It was done obliquely. On the lack of proper political direction, the committee quoted British India’s first Commander in Chief Field Marshal Robert’s dictum: “The art of war teach us not to rely on the likelihood of the enemy not coming, but on our own readiness to receive him; nor on the chance of not attacking but rather on the fact that we have made our position unassailable”.

“the Higher Direction of War and the actual command set-up of the Army were obviously out of touch with reality”.

There was another observation: “the Higher Direction of War and the actual command set-up of the Army were obviously out of touch with reality”. In a way, this was an indirect indictment of the political leadership and the manner in which the operations in NEFA had been handled. Chavan found these observations a very harsh judgment on Pandit Nehru’s handling of India’s relations with the People’s Republic of China and for which many felt at that time that he was so much wedded to the Panchsheel that he refused to believe that China had some other intentions. By accepting that comment publicly, he did not want to cause any more anguish to the Prime Minister who was already shattered by the perfidy of the China’s leadership in subscribing to the Panchsheel but all the time preparing to attack India.

At the same time, he did not want to formally reject this observation because that might further aggravate the morale of the very same senior officers on whom he depended to get the army into shape to face any future aggression. He decided to suppress those observations.Pradhan’s conclusions were that: “So far as the Parliament was concerned he [Chavan] performed so ably that at the end of the debate, the leader of the opposition profusely thanked him for his candid reply. That way, politically, Chavan established his own identity. He also earned trust and confidence of the Prime Minister for the manner in which he handled the most severe indictment that the Prime Minister had to face in his long parliamentarian career. The report was a grant education for the novice defence minister. He made copious notes in red ink to help him understand that military jargon. Those ‘two observations’ would offer guidelines to Chavan to shape his own role as Defence Minister. He also earned kudos of his service chiefs for not carrying ‘witch-hunt’. His relation of mutual trust to each one of them was crucial to conduct the 1965 War as evidenced in his Diary.”

The fact that “the report was a great education for the novice defence minister” is important to keep in mind, because it was the main purpose of the work of Herderson Brooks and Bhagat.

The Facts

On April 1, 1963 in reply to a question, the Defence Minister announced in Parliament that an inquiry into the conflict in NEFA had been instituted: “Thorough investigation had been ordered to find out what went wrong with:

For Chavan the main challenge in the first years was to establish relationship of trust between himself and the Prime Minister. He succeeded in doing so by his deft-handling of the Henderson Brooks Report”¦”

- our training;

- our equipment;

- our system of command;

- the physical fitness of our troops and

- the capacity of our Commanders at all levels to influence the men under them”.

There was no question of witch-hunting; the Report was just to help “derive military lessons” and “bring out clearly what were the mistakes or deficiencies in the past, so as to ensure that in future such mistakes are not repeated and such deficiencies are quickly made up”

The Defence Minister affirmed that the Army Headquarters had already [in April 1963] learned “from their observations — there are competent people there, professionally very able people — made their own studies about the problems and drawn certain lessons and efforts are being made on the basis of those lessons…”

He added that it was necessary to “improve the quality of planning for the campaigns and those well-thought-out plans will have to be backed by logistic supplies rather well-prepared in advance”.

He specifically mentioned the importance to have a closer understanding, collaboration and cooperation between the Army and the Air Force. He also said that “the physiological and psychological problems of acclimatization of troops at high altitudes were seriously engaging the attention of the Government”.

He pointed out that the Indian Army was “traditionally… trained and taught to think in terms of fighting on plains”, adding that closest relationship between officers and men were now being inculcated.

He stressed the importance of an intelligence system for the Army, “the machinery for intelligence cannot be created overnight. It required very thorough planning. It is a very complicated process… There is a feeling that there is no intelligence system in our country. Possibly this is a misunderstanding. There is a very effectively working intelligence system in India… We can claim to have our own eyes”.

The House was also informed that a chain of airfields was being constructed at various places of strategic importance.

The Inquiry Report17 was submitted to the Chief of the Army Staff on May 12. 1963. It was finally handed over to the Defence Minister on July 2.

At that time, Chavan stated in Parliament that the “the contents were not disclosed for considerations of security” and because they were likely to “affect the morale of those entrusted with safeguarding the security of our borders”.

On September 2, 1963, the Defence Minister spoke again and disclosed that the Inquiry Committee had not confined its investigations to the operations in NEFA alone but examined the “development and events prior to hostilities as also the plans, posture and the strength of the Army at the outbreak of hostility”. Further, a detailed review of the actual operations both in Ladakh and NEFA had been carried out “with reference to terrain, strategy, tactics and deployment of our troops”.

It is clear that the decision of Lt. Gen. Herderson Brooks and Brig. Bhagat to go into “development and events prior to hostilities as also the plans” embarrassed the Government18.

Summary of the Recommendations of the Report

In the Parliament, Chavan gave a summary of the main recommendations of the Report:

Training

It was found that “our basic training was sound and soldiers adapted themselves to the mountains adequately”. But troops had not been prepared for a war with China and hence they had “not requisite knowledge of the Chinese tactics and ways of war, their weapons, equipment and capabilities”.

There was “an overall shortage of equipment both for training and during operations”,

“Toughening and battle inoculations” were recommended, as also training in leadership” and correct “concept of mountain warfare”.

Equipment

There was “an overall shortage of equipment both for training and during operations”, though “the difficulty in many cases was that while the equipment could be reached to the last point in the plains or even beyond it, it was another matter to reach it in time, mostly by air or by animal or human transport, to the forward formations who took the brunt of fighting”. It further noted: “The speed with which troops were inducted from the plains to high altitudes and the lack of proper roads and other means of communication — road transport was both inadequate and weak for the steep gradients in mountainous terrain — added to the problems of logistics”. It was nevertheless stated that “our weapons were adequate to fight the Chinese and compared favourably with theirs”.

It was recommended that the deficiency in equipment, particularly equipment required for mountain warfare be made up and the modes of communication which could make the equipment available to the troops at the right place and at the right time be improved.

System of Command

‘Basically’ nothing was wrong with the system and chain of Command provided it was exercised in the accepted manner at various levels. It was revealed that “during the operations difficulties arose only when there was departure from accepted chain of Command”. Such departures occurred mainly owing to “haste and lack or adequate prior planning”. The Inquiry revealed “the practice that crept in the higher Army formations of interfering in tactical details even to the extent of detailing troops for specified tasks”.

Maxwell will elucidates about this tactical aspect.

Physical Fitness of Troops

It was encouraging to find that “our troops, both officers and men) stood the rigours of the climate, although most of them were rushed at short notice from plains. But it was stated “they were not acclimatized to fight at the heights at which some of them were asked to make a stand”.

Capacity of our Commanders

By and large, it was found that the “general standard amongst the junior officers was fair… At Brigade level, but for the odd exception, commanders were able to adequately exercise their command. It was at higher levels that shortcomings became more apparent.19 It was also revealed that some of the higher commanders did not depend enough on the initiative of the lower commanders…”

“ He (Chavan) also earned kudos of his service chiefs for not carrying “˜witch-hunt. His relation of mutual trust to each one of them was crucial to conduct the 1965 War as evidenced in his Diary.”

The Inquiry spent time on the question of military intelligence and procedures and higher direction of operations. The Committee’s conclusions were that “the collection of intelligence in general was not satisfactory. The acquisition of intelligence was slow and the reporting of it vague… The evaluation may not have been accurate”.

The field formations had little guidance on the Chinese build-up and troop deployment and movements. The Report further stressed that “much more attention will have to be given, than was done in the past, in the work and procedures of the General Staff at the Services Headquarters, as well as in the Command Headquarters and below, to long-term operational planning, including logistics as well as to the problems of co-ordination between various Services Headquarters “.

The Defence Minister told the Members of the Parliament that the reverses suffered by the Army during the 1962 operations were “due to a variety of causes and weaknesses”. The Chinese attack “was so sudden and in such remote and isolated sectors that the Indian Army as a whole was really not tested. In that period of less than two months… only about 24.000 of our troops were actually involved in fighting”.

Chavan also pointed out that in both Ladakh and Walong troops, fought with daring and courage20.

A week later the Defence Minister presented to Parliament a 3,500 word statement on defence preparedness. He confirmed that the “expansion of armed forces, expansion of their training facilities, modernization of their equipment and re-fitting them to step-up their operational efficiency’ was in progress.21

Forty-Seven Years Later

Today the Government is breaking its own laws to keep the Report as well as the entire corpus of related diplomatic correspondence, notes, briefings, and reports under wraps. Why?

Even if the founder of the post-independence dynasty, Jawaharlal Nehru may have emerged in bad light in the Herderson Brooks Report, why put a blanket on the entire archives?22 Are we living in a modern democracy?

…and this despite the fact that in 2005, the Right to Information Act was passed with fanfare by the Indian Parliament.

While Wikileaks daily provides us with fascinating details of the present NATO Af-Pak policy, the Government in Delhi is stuck on its antediluvian position; India is today one of the few nations which refuses to declassify archival material and this despite the fact that in 2005, the Right to Information Act was passed with fanfare by the Indian Parliament. In fact the law seems to have indirectly helped those who do not want India’s history to be known.

Article 8(1)(a) says: “There shall be no obligation to give any citizen, (a) information, disclosure of which would prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State, relation with foreign State or lead to incitement of an offense.”

This paragraph, interpreted by bureaucrats and politicians, is enough to make all the files of the Ministry of External Affairs, Defense, Home and PMO inaccessible to the general public.

The Neville Maxwell Interpretation

As we have seen from the dialogue between Nixon, Kissinger and Zhou Enlai, the only ‘authoritative’ source of information for the 1962 conflict seems to be Neville Maxwell. At first sight, this is logical since he is one of the few scholars or analysts to have read (and studied) the Herderson Brooks Report

In 2001, the author of India’s China War wrote a long paper in the Economic & Political Weekly: Henderson Brooks Report: An Introduction in which he elaborates on his theory: “When the Army’s report into its debacle in the border war was completed in 1963, the Indian government had good reason to keep it Top Secret and give only the vaguest, and largely misleading, indications of its contents. At that time, the government’s effort, ultimately successful, to convince the political public that the Chinese, with a sudden ‘unprovoked aggression’, had caught India unawares in a sort of Himalayan Pearl Harbour was in its early stages and the report’s cool and detailed analysis, if made public, would have shown that to be self-exculpatory mendacity.”

He (Chavan) stressed the importance of an intelligence system for the Army, “the machinery for intelligence cannot be created overnight. It required very thorough planning”¦”

For the past 45 years, this theory has gone around not only amongst the Chinese and US leaders23 but also some Indian intellectuals, that the conflict was triggered by Nehru’s policies, more particularly his Forward Policy.

Maxwell admits: “the report includes no surprises and its publication would be of little significance but for the fact that so many in India still cling to the soothing fantasy of a 1962 Chinese ‘aggression’. It seems likely now that the report will never be released. Furthermore, if one day a stable, confident and relaxed government in New Delhi should, miraculously appear and decide to clear out the cupboard and publish it, the text would be largely incomprehensible, the context, well known to the authors and therefore not spelled out, being now forgotten.”

Notwithstanding the fact that the British journalist believes that nobody has enough knowledge today to understand the background of the 1962 War, it is probably a fact that the Report itself does not contain anything really new24.

In his Introduction, Maxwell first goes into the ‘Origins of Border Conflict’ and explains: “But in the Indian political perspective war with China was deemed unthinkable and through the 1950s New Delhi’s defence planning and expenditure expressed that confidence. By the early 1950s, however, the Indian government, which is to say Nehru and his acolyte officials, had shaped and adopted a policy whose implementation would make armed conflict with China not only ‘thinkable’ but inevitable. From the first days of India’s independence, it was appreciated that the Sino-Indian borders had been left undefined by the departing British and that territorial disputes with China were part of India’s inheritance.”

Nobody disagrees with the first part of this statement: in the government circles, a conflict with China was unthinkable in the 1950’s25, but it is a wrong interpretation of the history to say that India “adopted a policy whose implementation would make armed conflict with China not only ‘thinkable’ but inevitable”. India merely took steps to defend her borders.

Nehru was naive, in the early 1950, he thought that there was no border issue. It was not the case for his Chinese counterpart.

I have written elsewhere on the issues of the Sino-Indian border dispute26, which, for Nehru was not ‘disputed’ or even ‘disputable’. Nehru was naïve, in the early 1950’s, he thought that there was no border issue. It was not the case for his Chinese counterpart. It is enough to quote the words of Zhou Enlai when the Panchsheel Agreement on Tibet was signed in April 1954, the Premier said: “all the issues ripe for settlement had been solved”. In other words, Zhou knew that the border issue was ‘unresolved’. The problem was not due to ‘India’s inheritance’ as Maxwell put it, but to Communist China’s new territorial claims, unknown to Nehru in 1954.

Maxwell put the onus of the non-settlement of the border dispute on the Nehru government: “India would through its own research determine the appropriate alignments of the Sino-Indian borders, extend its administration to make those good on the ground and then refuse to negotiate the result. Barring the inconceivable — that Beijing would allow India to impose China’s borders unilaterally and annex territory at will — Nehru’s policy thus willed conflict without foreseeing it. Through the 1950s, that policy generated friction along the borders and so bred and steadily increased distrust, growing into hostility, between the neighbours.”

Where Maxwell is wrong is when he says that India: “began accusing China of committing ‘aggression’ by refusing to surrender to Indian claims.”

That Nehru did not claim areas like Aksai Chin before 1958 is a fact28, but how does it make it a Chinese territory?

Therefore Maxwell’s argument is erroneous when he says: “From 1961 the Indian attempt to establish an armed presence in all the territory it claimed and then extrude the Chinese was being exerted by the Army and Beijing was warning that if India did not desist from its expansionist thrust, Chinese forces would have to hit back.”

The Chinese knew fairly well that India was not prepared. By 1962, Beijing had collected extensive intelligence, particularly amongst the Monpa population of NEFA; they were fully aware of the total lack of preparation on the Indian side.

The expansionist thrust has always been a Chinese trait, though nobody can deny that it was pure folly from Nehru’s part to announce ‘India’s intention to drive the Chinese out of areas India claimed’ on October 12, 1962, without adequate preparations.

The British author further elaborates on his own theory: “That bravado had by then been forced upon him by the public expectations which his charges of ‘Chinese aggression’ had aroused, but Beijing took it as in effect a declaration of war. The unfortunate Indian troops on the front line, under orders to sweep superior Chinese forces out of their impregnable, dominating positions, instantly appreciated the implications”.

Maxwell’s theory, “If Nehru had declared his intention to attack, then the Chinese were not going to wait to be attacked”, does not stand scrutiny.

The Chinese knew fairly well that India was not prepared. By 1962, Beijing had collected extensive intelligence, particularly amongst the Monpa population of NEFA; they were fully aware of the total lack of preparation on the Indian side. The fact that ‘they were not going to wait’ was probably linked rather with the internal situation in China and the catastrophic outcomes of the Great Leap Forward.

Mao Zedong knew that the time had come to teach India a lesson, thereby regaining the upper hand in the internal power struggle in China29.

In a section called Factionalisation of the Army, Maxwell is probably closer to the truth in his assessment. He speaks in details of the negative role played by Lt Gen BM Kaul: “At the time of independence Kaul appeared to be a failed officer, if not disgraced. Although Sandhurst-trained for infantry service, he had eased through the war without serving on any frontline and ended it in a humble and obscure post in public relations. But his courtier wiles, irrelevant or damning until then, were to serve him brilliantly in the new order that independence brought, after he came to the notice of Nehru, a fellow Kashmiri brahmin and indeed distant kinsman. Boosted by the Prime Minister’s steady favouritism, Kaul rocketed up through the army structure to emerge in 1961 at the very summit of Army HQ. Not only did he hold the key appointment of chief of the general staff (CGS) but the Army Commander, Thapar, was in effect his client. Kaul had of course by then acquired a significant following, disparaged by the other side as ‘Kaul boys’ (‘call girls’ had just entered usage) and his appointment as CGS opened a putsch in HQ, an eviction of the old guard, with his rivals, until then his superiors, being not only pushed out, but often hounded thereafter with charges of disloyalty. The struggle between those factions both fed on and fed into the strains placed on the Army by the government’s contradictory and hypocritical policies — on the one hand proclaiming China an eternal friend against whom it was unnecessary to arm, on the other using armed force to seize territory it knew China regarded as its own.”The extensive infrastructure network, the state of preparedness of the Chinese troops, the easiness with which they penetrated some sectors such as West Kameng (Tawang) are ample proofs that they had prepared since years for the attack of October 1962. It had nothing to do with the 1961 Forward Policy.

Maxwell argues that Nehru’s ‘covertly expansionist’ policy was implemented by the Intelligence Bureau (IB) Chief BN Mullik, ‘another favourite and confidant of the Prime Minister’.

Maxwell argues that Nehru’s ‘covertly expansionist’ policy was implemented by the Intelligence Bureau (IB) Chief BN Mullik, ‘another favourite and confidant of the Prime Minister’. Maxwell writes: “The Army high command, knowing its forces to be too weak to risk conflict with China, would have nothing to do with it. Indeed when the potential for Sino-Indian conflict inherent in Mullik’s aggressive forward patrolling was demonstrated in the serious clash at the Kongka Pass in October 195930, Army HQ and the Ministry of External Affairs united to denounce him as a provocateur, insist that control over all activities on the border be assumed by the Army, which thus could insulate China from Mullik’s jabs.”

According to Maxwell, the turning point was the ‘takeover’ by Kaul and his ‘boys’ at Army HQ in 1961. Regular jawans took over from the IB’s border police to implement the ‘forward policy’.

Maxwell says: “Field commanders receiving orders to move troops forward into territory the Chinese both held and regarded as their own, warned that they had no resources or reserves to meet the forceful reaction they knew must be the ultimate outcome: They were told to keep quiet and obey orders.”

The rest is history. Maxwell rightly notes: “China’s stunning and humiliating victory brought about an immediate reversal of fortune between the Army factions. Out went Kaul, out went Thapar, out went many of their adherents — but by no means all. …Political interference in promotions and appointments by the Prime Minister and Krishna Menon, defence minister, followed by clownish ineptitude in Army HQ as the ‘Kaul boys’ scurried to force the troops to carry out the mad tactics and strategy laid down by the government.”

The Report according to Maxwell

Maxwell says it is a rather long document with a main section, recommendations and several annexures. It covers more than 200 foolscap pages.

Maxwell affirms that the two-member Committee went beyond its brief, explaining thus the need to give the highest classification to their Report: “Henderson Brooks and Baghat in effect ignored the constraints of their terms of reference and kicked against other limits Chaudhuri had laid upon their investigation, especially his ruling that the functioning of Army HQ during the crisis lay outside their purview. “It would have been convenient and logical”, they note, “to trace the events [beginning with] Army HQ, and then move down to Commands for more details …ending up with field formations for the battle itself”.

Apparently, Lt Gen Herderson Brooks faced ‘determined obstruction in Army HQ’. According to the British journalist, the reason was that “one of the leading lights of the Kaul faction had survived in the key post of Director of Military Operations (DMO) — Brigadier DK Palit. Kaul had exerted his powers to have Palit made DMO in 1961 although others senior to him were listed for the post”.

In that period of less than two months only about 24,000 of our troops were actually involved in fighting”.

For Maxwell, Palit was the “enforcer for Kaul and the civilian protagonists of the ‘forward policy’, Mullik foremost among the latter, issuing the orders and deflecting or overruling the protests of field commanders who reported up their strategic imbecility or operational impossibility”.

The Forward Policy had come into existence at a meeting chaired by the Prime Minister on November 2, 1961, though Maxwell believes that it was “alive and kicking in the womb for years before that”. He mentions the year 1954 when Nehru first realized the importance to man the borders31. Earlier in history, when Tibet a ‘de facto’ independent country, it had not been necessary.

The Report noted that no minutes of the famous meeting were available, though Mullik was quoted as saying: “the Chinese would not react to our establishing new posts and that they were not likely to use force against any of our posts even if they were in a position to do so” It appears that this contradicted the conclusions that the Army Intelligence had reached 12 months earlier, namely that the Chinese would resist by force any attempts to take back territory held by them. The Report also pointed out the contradiction between the position of the Army HQ and the Western Command, when the HQ ordered “the establishment of ‘pennypacket’ forward posts in Ladakh, specifying their location and strength and Western Command protesting that it lacked the forces to carry out the allotted task, still less to face the grimly foreseeable consequences.”

There is no doubt that the assumption that the Chinese would not resist using force was wrong; history has proven this beyond doubt.

That Nehru did not claim areas like Aksai Chin before 1958 is a fact, but how does it make it a Chinese territory?

According to the Report, from the beginning of 1961 crucial professional military practice was abandoned:32 “From this stemmed the unpreparedness and the unbalance of our forces. These appointments in General Staff are key appointments and officers were hand-picked by General Kaul to fill them.”

In a section War and Debacle, Maxwell points again to the Forward Policy which began to be operative in December 1961 in the Eastern Sector and particularly near the Dhola Post, which the Chinese33 considered to be their territory, while India believed that the area was part of India. For Maxwell, the Indian action in this area was a provocation.

More interesting is the antagonism between the Army HQ (in this case, Eastern Command headed by Lt Gen LP Sen) and the local commanders, Lt Gen Umrao Singh (XXXIII Corps), Major General Niranjan Prasad (4 Division) and Brigadier John Dalvi (7 Brigade). The ‘local’ officers agreed that the ‘attack and evict’ order was militarily impossible to execute and the area below Thagla Ridge (at the western extremity of the McMahon Line), presented too many logistical difficulties. Quoting the Report, Maxwell writes: “so whatever concentration of troops could painfully be mustered by the Indians could instantly be outnumbered and outweighed in weaponry”.

No minutes of meetings

One of the difficulties faced by the members of the Inquiry was there were no minutes of the crucial meetings. At the same time, the Committee recorded its surprise that the most secret decisions of the government were immediately reported in the press.34

There is no doubt that the assumption that the Chinese would not resist using force was wrong; history has proven this beyond doubt.

Krishna Menon, the then Defence Minister, had requested that “in view of the top secret nature of conferences no minutes would be kept [and] this practice was followed at all the conferences that were held by the defence minister in connection with these operations”.

To say that this is astonishing would be an understatement. The Committee commented: “This is a surprising decision and one which could and did lead to grave consequences. It absolved in the ultimate analysis anyone of the responsibility for any major decision. Thus it could and did lead to decisions being taken without careful and considered thought on the consequences of those decisions”.

Howeverm what is the point in hiding this today, nearly fifty years after the incident, when so much has been written on the arrogant Defence Minister.

Another issue highlighted by the Report is the Army HQ interference in local issues of which they had no knowledge. For example, in mid-September 1962, an order was issued to troops beneath Thagla Ridge to “(a) capture a Chinese post 1,000 yards north-east of Dhola Post; (b) contain the Chinese concentration south of Thagla.”

The Report observed: “The General Staff, sitting in Delhi, ordering an action against a position 1,000 yards north-east of Dhola Post is astounding. The country was not known, the enemy situation vague and for all that there may have been a ravine in between [the troops and their objective], but yet the order was given. This order could go down in the annals of history as being as incredible as the order for the Charge of the Light Brigade”.

The extensive infrastructure network, the state of preparedness of the Chinese troops, the easiness with which they penetrated some sectors such as West Kameng (Tawang) are ample proofs that they had prepared since years for the attack of October 1962.

Next a new Corps (IV Corps) was formed; Umrao Singh retained his command but the new Corps was now responsible to evict the Chinese and drive them off the Thagla Ridge. Lt Gen Kaul was given the job.

According to the Report, this was done with “wanton disregard of the elementary principles of war”.

Maxwell writes that the “account of the moves that preceded the final Chinese assault is dramatic and riveting, with the scene of action shifting from the banks of the Namka Chu, beneath the menacing loom of Thagla Ridge, to Nehru’s house in Delhi — whither Kaul rushed back to report when a rash foray he had ordered was crushed by a fierce Chinese reaction on October 10. To follow those events, and on into the greater drama of the ensuing debacle is tempting, but would add only greater detail to the account already published. Given the nature of the dramatic events they were investigating, it is not surprising that [the Report] cast of characters consisted in the main of fools and/or knaves on the one hand, their victims on the other. But they singled out a few heroes too, especially the jawans, who fought whenever their senior commanders gave them the necessary leadership, and suffered miserably from the latter’s often gross incompetence.”

Unless one reads the Report, it is difficult to say if it is ‘dramatic and riveting’.

Why to keep the Report Secret?

We are living in the Wikileaks era, but the Herderson Brooks Report is still ‘classified’. Even the Secret Archives of the Vatican will soon be opened. Nick Squires recently wrote in The Telegraph: “After centuries of being kept under lock and key, the Vatican has started opening its Secret Archives to outsiders in a bid to dispel the myths and mystique created by works of fiction such as Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons.”35

It is not the Ministry of Defense alone which is guilty of confiscating India’s history. The Times of India reported: “What steps does the government follow while deciding to declassify its old secret documents? You may never get to know since the manual that details the declassification process in the country is itself marked confidential.36” The PMO alone has admitted having 28,685 secret files, not one has been declassified in the recent years.

Even if the government officially swears by the rule to make files public after 20 or 25 years, the policy remains unimplemented.

Ironically, the Chinese government is much more open. The Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson Center in the US has recently “obtained a large collection of Chinese documents detailing Beijing’s foreign policy surrounding the Sino-Indian Border clashes [1962 War]”. The documents will soon be posted on the CWIHP website.

It means that scholars will soon be able to research the 1962 conflict from a Chinese point of view, but still not from the Indian one.

Though the entire ‘classification’ exercise is clearly to protect the first Prime Minister of India, one wonders how many in India have ever read what Jawaharlal Nehru himself wrote on the subject.

One of these angles is the internal struggles within China between 1959 and 1962 and the role of Mao Zedong during these crucial years. A study of the Russian and East European archives, already partially opened, throws new light on the real motivation for the Chinese attack.

Though the entire ‘classification’ exercise is clearly to protect the first Prime Minister of India, one wonders how many in India have ever read what Jawaharlal Nehru himself wrote on the subject.

On 27 August 1957, in a Note to his Principal Private Secretary (PPS), the first Prime Minister of India commented about some persons having been refused access to the National Archives of India: “The papers required are very old, probably over thirty years old. No question of secrecy should apply to such papers, unless there is some very extraordinary reason in regard to a particular document. In fact, they should be considered, more or less, public papers. …I do not particularly fancy this hush hush policy about old public documents. Nor do I understand how our relations with the British Government might be affected by these as PPS has somewhere stated.”37

The Central Information Commission

In 2007, former MP and veteran journalist Kuldip Nayar took the matter to the Central Information Commission, under the Right to Information Act 2005. The Respondent, the Ministry of Defence dragged its feet for months and tried to take refuge behind the Section 8(1).

The CIC had to clarify: “Under the above circumstances we cannot accept an argument simply stating that the information sought stands exempted. Since in addition to Section 8(1) there is also Section 8(2) that empowers the Public Authority to take a decision in the matter, if it concerns the public interest. This Section reads as follows: 8(2) notwithstanding anything in the Official Secrets Act, 1923 or any of the exemptions permissible in accordance with sub-section (1), a public authority may allow access to information, if public interest in disclosure outweighs the harm to the protected interests.”

The stand of the Defence Ministry was explicitly given during a hearing of the Commission on March 7, 2009: “It was submitted by Col Raj Shukla that the report prepared by Lt Gen Henderson Brooks and Brig Prem Bhagat was a part of internal review conducted on the orders of the then Chief of Army Staff, Gen Choudhary. Reports of internal review are not even submitted to Govt. let alone placed in the public domain. Disclosure of this information will amount to disclosure of the army’s operational strategy in the North-East and the discussion on deployments has a direct bearing on the question of the demarcation of the Line of Actual Control between India and China, a live issue under examination between the two countries at present. The Director General, Military Operations, therefore, submitted that the report falls clearly within the exemption of disclosures laid down in sec. 8(1)(a) of the RTI Act read with Sec. 8(3). After a presentation by Col Shukla we then inspected the original report, which had been placed before us, including the conclusion contained in pages 199 to 222 of the main report.”

Krishna Menon, the then Defence Minister, had requested that “in view of the top secret nature of conferences no minutes would be kept”

In a ‘decision notice’ dated March 19, 2010, the Commission said38: “We have examined the report specifically in terms of its bearing on present national security. There is no doubt that the issue of the India-China Border particularly along the North East parts of India is still a live issue with ongoing negotiations between the two countries on this matter. The disclosure of information of which the Henderson Brooks report carries considerable detail on what precipitated the war of 1962 between India and China will seriously compromise both security and the relationship between India & China, thus having a bearing both on internal and external security. We have examined the report from the point of view of severability u/s 10(1). For reasons that we consider unwise to discuss in this Decision Notice, this Division Bench agrees that no part of the report might at this stage be disclosed.”

It means that practically it is Neville Maxwell’s interpretation which will continue to prevail.

Some conclusions

While it is not our purpose to discuss the order of the Commission, it should be pointed out that all over the world, the normal practice is to ‘sanitize’ (or blacken) details which cannot be disclosed, for whatever reasons.

It is commonly done by the US State Department and the CIA (for example in the ‘POLO’ history of the Sino-Indian Conflict quoted above) or other governments. It could have easily been done (and still can be done) for the Herderson Brooks Report.

Further, Lt Gen Herderson Brooks and Brigadier Bhagat were not infallible. They may well have wrongly assessed some details (about the border issue in particular); continuing to hide the Report tends to prove that they found some truth which the general public should not know about.

To pretend that the ‘disclosure of this information will amount to disclosure of the army’s operational strategy in the North-East’ is not even worth discussing.

Regarding the border being a live issue, if some portions of the Report do not tally with the present position of the Government of India, it could very well be sanitized or explained that the view of the Inquiry Committee was not (and is not) that of the Government.

The release of the Report would certainly trigger further historical research on the subject, particularly in view of the opening of the US, Russian and Chinese archives. Today, as we have seen in the opening paras, Neville Maxwell’s interpretation alone is ‘authoritative’. This is unfortunate for India.

In my opinion, by keeping the Report under wraps, the Government is doing a disservice to the nation.

Notes

- Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs.

- John H. Holdridge was working with Henry A. Kissinger.

- Winston Lord was also on Kissinger’s staff.

- Known as the Panchsheel Agreement, the actual title is “Agreement between The Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China on Trade and Intercourse between Tibet Region of China and India”. It was signed on April 29, 1954.

- This is not a fact: the addition of the Five Principles as a Preamble was an idea of K.M. Panikkar, the Indian Ambassador, but it benefited China, particularly the ‘non-interference in internal affairs’ clause. Beijing could now say “Tibet is our internal affair, do not interfere”.

- Neville Maxwell, India’s China War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1970).

- Zhou continued about the Soviet Union’s role in the 1962 war: “In looking at 1962, the events actually began in 1959. Why did he go to Camp David? In June of that year, before he went to Camp David, [Khrushchev] unilaterally tore up the nuclear agreements between China and the Soviet Union. And after that there were clashes between Chinese and Indian troops in the western part of Sinkiang, the Aksai Chin area. In that part of Sinkiang province there is a high plateau. The Indian-occupied territory was at the foot of the Karakorums, and the disputed territory was on the slope between.” Kissinger intervened to ask: “It’s what they call Ladakh,” Nixon commented: “They attacked up the mountain!” Zhou Enlai then explained to his American guests: “We fought them and beat them back, with many wounded. But the TASS Agency said that China had committed aggression against India. After saying that, Khrushchev went to Camp David. And after he came back from Camp David he went to Peking [Beijing], where he had a banquet in the Great Hall of the People. The day after the banquet he went to see Chairman Mao. Our two sides met in a meeting.” “At that time our Foreign Minister was Marshal Chen Yi, who has now passed away. Marshal Chen Yi asked him: “Why didn’t you ask us before releasing your news account? Why did you rely on the Indian press over the Chinese press? Wasn’t that a case of believing in India more than us, a fraternal country?” “And what did Khrushchev say? ‘You are a Marshal and I am only a Lieutenant General, so I will not debate with you.’ He was also soured, and did not shake hands when he left. But he had no answer to that. He was slightly more polite to me.”

- Prepared by the History Division of the Ministry of Defence under the editorship of S.N. Prasad.

- Yashwantrao Balwantrao Chavan (12 March 1913 - 25 November 1984) was the first Chief Minister of Maharashtra after the division of Bombay State and the fifth Deputy Prime Minister of India. He was Defence Minister from November 21, 1962 till 1965.

No comments:

Post a Comment