NAIN SINGH RAWAT (1830-95)

Posted by Surjit on Feb 14th, 2013 in Wanderlust and Travelogues

By Joseph Thomas

Only those who have marched

through the Himalayas know how difficult it is to march from one place

to another. It was even more difficult when people did not have proper

maps and other navigation aids. During my service in Bhutan and Sikkim I

got a taste of the hazards of this challenge. Sometimes, a neighboring

peak or ridge which appeared to be no more than a kilometer away, took a

whole day to reach, because one had to descend a few thousand feet and

then climb back on a long and tortuous path. In Sikkim, I heard of the

expeditions of Lt Col Sir FE Young Husband (1863-1942). He made discovered some excellent routes to Tibet. My friend, Wg Cdr Joseph Thomas, VM has flown over the area extensively and taken aerial pictures of the entire range. Despite being a Pilot, Thomas has his feet firmly on the ground. He has been reading about Pundit Nain Singh Rawat who explored these routes more than 160 years ago, when the logistics were even more primitive. For those who care to read about this gallant son of India, he has sent me the following piece for ‘guftagu’

For those who may not know, Thomas topped the entrance order of merit to the XIX NDA course, and retained that position all through the six terms. He passed out with the silver medal. Later, he was trained as a test pilot in the USA and commanded the ‘air photo’ squadron of the IAF. You see a recent picture of Joseph Thomas on top of this post (it is customary in this blog to give the author’s picture.You see him at the bottom of this piece, looking like an explorer himself!) the mail ID of Thomas is himlynx@gmail.com. Incidentally his mail ID is a symbol of the IAF squadron which he commanded.

*

When I first mentioned Nain Singh, Surjit asked “Who was Nain Singh ?”

While awarding the Patron’s medal in

1877, the Royal Geographic Society said “either of his great journeys

in Tibet would have brought this reward to any European explorer; to

have made two such journeys adding so enormously to accurate knowledge .

. . is what no European but the first rank of travelers like

Livingstone or Grant have done . . . . His observations have added a

larger amount of important knowledge to the map of Asia than those of

any other living man.”

Yet, Nain Singh Rawat is little known

outside of the small world of Indian surveyors. So this is a tribute to

a great but little known surveyor.

Born in 1830, Nain Singh’s early

education was mostly at home. Subsequently, he helped his father in

their traditional trans-border trade with Tibet. He visited several

trade centres in Tibet, learnt the Tibetan language, customs and

manners, and became familiar with the Tibetan people. This knowledge

helped Nain Singh during his future survey missions. . Later he became a

school teacher in the village of Milam in the Upper Himalayas.

In 1863 Nain Singh and his older cousin, Mani Singh joined the Survey

of India and trained as surveyors. They were taught to walk at a

constant pace of 33 inches. To keep track of the number of paces, they

were given rosaries, with 100 beads instead of the traditional 108.

One complete circuit of the rosary would mean 10, 000 paces and

measure 5 miles!Nain Singh’s pilgrim outfit had other special modifications. His tea bowl had a false bottom which stored mercury that helped him find the horizon. His walking stick hid a thermometer, which he would dip into tea water just as it came to a boil and thus determine the altitude. This method got him the altitude of Lhasa within 10 %.

The biggest sacrilege, though, was Nain Singh’s prayer wheel. A prayer wheel is a holy object stuffed with scrolls of the Tibetan mantra Om! Mane Padme Hum! However, inside Nain Singh’s divine prayer wheel were hidden his route survey, careful notes that showed altitudes, landmarks, and the distances that he walked. These barefoot surveyors were given code names – Nain Singh was the Chief Pundit and his cousin, the Second Pundit. These codes stuck and all later surveyors were called Pundits.

In 1865, Nain Singh and Mani Singh left Dehra Dun, the Survey of India’s headquarters, for Nepal. From there Mani returned to India by way of western Tibet, but Nain went on to Tashilhunpo, Shigatse, where he met the Panchen Lama, and Lhasa, where he met the Dalai Lama.

An old Painting of Lhasa

Lhasa, as it looks today

During his stay in Lhasa, his true identity was discovered by two

Kashmiri merchants residing at Lhasa, but not only did they not report

him to the authorities, they lent him a small sum of money against the

pledge of his watch. Nain Singh returned to India by way of Mansarowar

Lake in western Tibet.

On a second expedition, in 1867, Singh explored western Tibet and visited the legendary Thok Jalung gold mines. He noticed that the workers only dug for gold near the surface, because they believed digging deeper was a crime against the Earth and would deprive it of its fertility.

The Rawat family had made very substantial contributions to the exploration of Tibet between 1865 and 1872. The journeys of Nain, Mani and Kal ian had crisscrossed much of the Southwestern corner of the country, while Nain had mapped southern Tibet along the Tsangpo and north of the river to Lhasa. Kishen had done a route survey north of Lhasa for over a hundred miles to Tengri Nor and the Bul Lake.

On a second expedition, in 1867, Singh explored western Tibet and visited the legendary Thok Jalung gold mines. He noticed that the workers only dug for gold near the surface, because they believed digging deeper was a crime against the Earth and would deprive it of its fertility.

N AI N S I N GH ’ S LAS T M AJ OR S U R V EY E XP ED I TI ON

The Rawat family had made very substantial contributions to the exploration of Tibet between 1865 and 1872. The journeys of Nain, Mani and Kal ian had crisscrossed much of the Southwestern corner of the country, while Nain had mapped southern Tibet along the Tsangpo and north of the river to Lhasa. Kishen had done a route survey north of Lhasa for over a hundred miles to Tengri Nor and the Bul Lake.

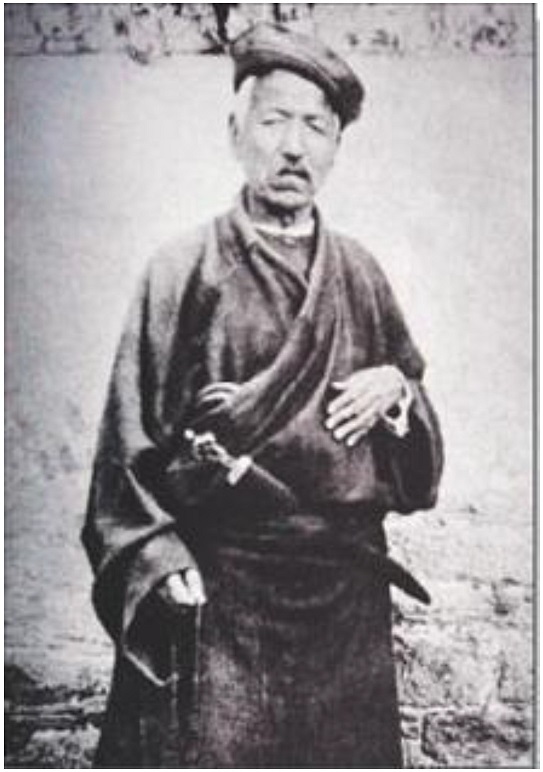

Rai Bahadur Kishan Singh Rawat (1850-1921)

But most of Tibet still remained unvisited and unmapped. Between Tengri Nor and the Nganglaring Tso of Kalian Singh stretched over four hundred miles of virgin territory, quite unvisited, as were the

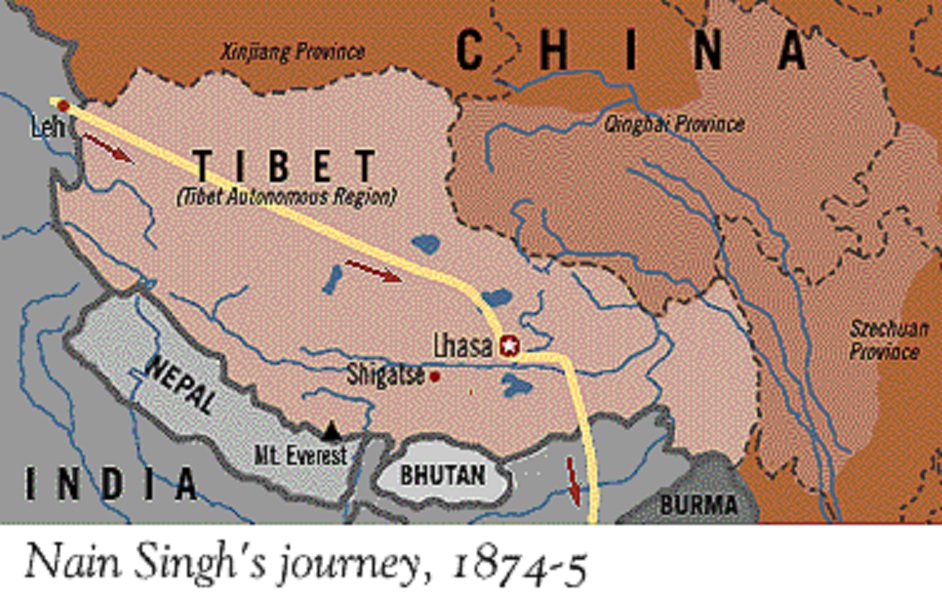

further reaches of northern Tibet. In 1874 came the opportunity to penetrate this area, to map fresh territory, and to provide a new link between Lhasa and the surveys already conducted in Southwestern Tibet.

The objectives of this last journey were to survey a route from Leh to Lhasa by a much more northerly path than the one he had taken in 1865. This was Nain Singh’s third clandestine penetration of Tibet. He carried sufficient cash with him for the journey upto Lhasa. But to carry more, even in the form of merchandise, through areas infested by robbers was risky. As it happened, the triennial Lopchak mission from Ladakh to Lhasa was about to leave Leh. Nain Singh had traveled with this caravan before, and the Lopchak agreed to take money to Lhasa for him. Since the caravan was a large one and traveled along a well-known road, it was felt that this arrangement would provide ample security.

Nain Singh’s party included four attendants. One was his servant Chumbel, two were Tibetans who had also accompanied him in the past, and the fourth was a Ladakhi, loaned by the headman of Tankse village. A flock of sheep served as pack animals. They set out from Leh on 15 July 1874, Nain Singh leaving behind the impression that he was going to Yarkand.

Nine days later they reached the last Ladakhi village, and under cover of darkness, slipped through. At first they did follow the Changchenmo road north, but after two days turned east. Slow progress was made, the pace determined by the speed of the sheep. The party was now in Tibet, on the north bank of Lake Pangong, and proceeding in a generally southeast direction, parallel to th e Tsangpo but at distances varying from one hundred to two hundred miles north of the course of the river.

Pangong Lake. It’s half in India and half in Tibet. Its water is crystal clear,and yet, awefully salty.

The villager from Tankse had gone ahead of them and by using his good offices had obtained from the local officials the permission needed to proceed into the heart of Tibet. Nain Singh continued past Lake Pangong and was able to fix the location of its eastern extremity.

Nain Singh’s route now took him on to the great lacustrine plain of central Tibet. Most of the lakes were salt, but some were fresh water and the travelers wer e able to fill their waterskins. For the first ten days the road was not far to the north of the route taken by Kalian Singh while on his way from Rudok to the gold mines of Thok Jalung.

For security, they would deliberately camp well off the road, to avoid robbers whose favorite trick was to cut the tent ropes at night and plunder the camp. The altitude was, on average, a little over fourteen thousand feet. A few shepherds were seen, but the paucity of human population was more than made up for by an abundance of animal life.

About one-third of the way between Lake Pangong and Tengri Nor, Nain Singh entered an area inhabited by Khampas, who said that they had migrated there from Kham (north and east of Lhasa) twenty-five years earlier. Accomplished horsemen and sportsmen, they tended herds of horses, sheep, and goats. They also had a bad reputation for plundering caravans. However, because one of his servants had befriended one of the Khampas in Ladakh some years before, Nain Singh was able to join a small group of them going in the same direction, and which afforded some protection for a while. Then, taking a devious route to minimize the risk of being robbed, they arrived in the gold-mining area of central Tibet.

Nain Singh found that the amount of gold produced was so small that the local shepherds were wealthier than the gold diggers. Pausing for just one day at the gold mines, Nain Singh and his companions, continued across the Chang Tang.

Tibetan Antelopes (Chiru) in Chang Tang. The famous Shahtoosh shawls are woven with its down hair.

Their altitude was now sixteen thousand feet, but the sun was warm, grass grew underfoot, and herds of antelope grazed nearby. On his route from Lake Pangong, Nain Singh had been marching parallel to a snowy range lying just to the south, a chain of mountains now known as the Nain Singh Range.

Their altitude was now sixteen thousand feet, but the sun was warm, grass grew underfoot, and herds of antelope grazed nearby. On his route from Lake Pangong, Nain Singh had been marching parallel to a snowy range lying just to the south, a chain of mountains now known as the Nain Singh Range.

Another lake in Central tibet

Nain Singh struck the northwest comer of Tengri Nor (the easternmost point of which is about eighty miles due north of Lhasa), after a journey of sixty -four marches from Noh, near Lake Pangong. He had mapped a chain of lakes across central Tibet, none of which had been seen before. Only Tengri Nor itself had been visited before by a trans-Himalayan explorer, in 1872, when Kishen Singh made a complete tour around it.

Tengri Nor (now called Nam Tso)

Nain Singh followed the path of Kishen Singh along the northern shore of Tengri Nor for fifty miles and then, like his predecessor, turned to the south in the direction of Lhasa. After some ten to twenty miles, he struck off by a different and less direct route to the Tibetan capital.

The party entered Lhasa on 18 Nov 1874, averaging just under ten miles per day over the 1,095 miles from Leh. But the sheep purchased in Ladakh, although slow movers, had more than proved their worth. Of the twenty-six that started out on the journey, four or five covered the entire distance.

Others were eaten or had been taken sick. All carried twenty to twenty-five pounds of baggage on their backs and foraged for whatever food they could get.

Nain Singh was anticipating small luxuries such as fresh vegetables, beer, and a more comfortable accommodation in Lhasa. Unfortunately, this was not to be. He sent one of his servants ahead to see if the Lopchak mission had arrived with the remainder of his funds. The response was negative; in fact, the head of the mission had died on the way to Lhasa. But there was a more present danger. On reaching Lhasa, Nain Singh had the bad luck to bump into a merchant from Leh who knew his identity and true occupation. Nain Singh feared betrayal and made plans to leave Lhasa immediately, rather than wait in the hope that the Lopchak mission might appear. Had he been able to delay his departure, he might have been able to retrieve his funds from the mission, even in the absence of the Lopchak himself.

Instead, Nain Singh sent two of his men back to Leh. They carried details of all his astronomical observations and route survey, and they reached safely in January 1875. Nain Singh left Lhasa abruptly with his two remaining servants only two days after arriving. In order not to arouse suspicion, and to throw pursuers off the track should he be betrayed, Nain Singh left his bulky inessentials behind with his landlord, saying that he would collect them in a month’s time after returning from a pilgrimage to a monastery north of Lhasa. The small party duly left Lhasa for the north, but as soon as darkness fell made a 180-degree turn toward India.

A week after leaving Lhasa, Nain Singh reached the Tsangpo, followed it for two days and then crossed it by boat near the town of Chetang. The river was sluggish, and he was able to estimate its speed as two-thirds of a mile per hour by throwing in a piece of wood and timing it over a fixed distance. Measuring the poles used to punt the ferry across the river gave it a depth of between eighteen and twenty feet. The river was about five hundred yards wide.

Chetang was fifty miles beyond the lowest point at which the river had been mapped to date, and from the town Nain Singh was able to approximate its course for a further one hundred miles by taking bearings of distant peaks, the Tsangpo being reputed to pass to one side of them.

Following the road south away from the Tsangpo, and up the valley of the Yarlung, one of its tributaries, Nain Singh crossed the main Himalayan chain by the Karkang pass, at a height of over sixteen thousand feet. He was traveling toward Tawang, accompanied by a man of some importance in that district. The merchants of Tawang were suffering at the hands of those in Lhasa and so were preventing any merchants from Tibet from proceeding onward to the Indian border, in order to retain the bulk of the trade for themselves. Because of this, Nain Singh was detained in Tawang from 24

December until 17 February. Eventually, by depositing almost all of his remaining goods and by claiming that he would return for them after a pilgrimage just across the border, he reached Udaiguri in Assam on 1 March 1875. There he presented himself to the local assistant commander, who made travel arrangements for Nain Singh to proceed to Gauhati. There he once again met up with the Tsangpo, now known as the Brahmaputra, and took a steamer to Calcutta.

The expedition had achieved important results. Nain Singh had traveled 1,405 miles between Leh and Udaiguri. His survey had started at Noh, a village whose position had also been fixed by Kish en Singh. It terminated at Udaiguri, the position of which was known very accurately from measurements made by the Indian Revenue Survey Department. Between these two points stretched 1,319 miles of virtually unknown country, of which 1,200 miles was completely unexplored. Prior to Nain Singh, only the small section around Tengri Nor had been surveyed, by Kishen Singh in 1872.

Nain Singh had located the eastern extremity of Lake Pangong, provided additional details of theTibetan goldfields, mapped a large number of new lakes and rivers, and confirmed the existence of a chain of snow peaks to the north of the Tsangpo. More information on the course of this river through Tibet had been discovered. The route through Tawang to Assam had been charted for the first time.

Nain Singh also took a large number of sextant observations, as well as pacing his route, taking compass bearings and measuring for altitude by observing the boiling point of water. All had to be made in conditions of complete secrecy .

No Europeans were successful in reaching Tengri Nor until 1890. A British expedition to the west of Tengri Nor almost half a century after Nain Singh commented that most of the information they had on the area was still derived from his expedition and that of Kishen Singh.

This was Nain Singh’s final foray beyond the frontiers. The stress of this journey and prolonged exposure to the elements had taken their toll on his health, and his eyesight in particular had been affected by continuous observations without snow goggles taken at very high altitudes. But although he retired from exploration, he continued to serve the Indian government with the traini ng of younger explorers.

Nain Singh’s name was now made public and was announced in the Geographical Magazine in 1876. In recognition of his prodigious feats of exploration, Nain Singh was presented with an inscribed gold chronometer by the Royal Geographic Society (RGS) in 1868. The Victoria or Patron’s Medal followed in 1877. The Society of Geographers of Paris also awarded Nain Singh an inscribed watch. The Government of India bestowed two villages as a land-grant to him.

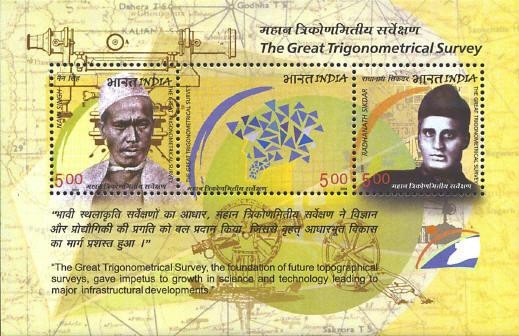

A postage stamp was issued in 2004 commemorating his role in the Great Trigonometrical Survey.

Nain Singh Rawat died of a heart attack in 1895, while visiting his jagir.

A recent book entitled “Asia Ki Peeth Par : Pundit Nain Singh Rawat”

by Uma Bhatt & Shekhar Pathak, PAHAR, Nainital was published,

containing an extensive account of his expeditions in 2006.

Views of Nain Singh’s home district of Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand today.

Indeed, Nain Singh has left an indelible imprint on the sands of time. The likes of Surjit who have not heard of him need to be educated. His work is no less significant than what Sir George Everest and Sir Young Husband did. Nain Singh deserves to be recognized as a gallant son of India.

The Author

Given below is a recent picture of Wg Cdr Joseph Thomas. He looks like an explorer himself!

No comments:

Post a Comment